Dancing at the Edge of Chaos: Finding Stability Through Change

An introduction to models of the human mind

In Brief

This is the first post in a series that will build on a theme reflecting my firm belief that how we think is the key to understanding what we think.

Future posts will explore models of the mind that will help you understand the working of your mind, as well as the mental models of others. These models are science-based, but presented in plain English.

In this post, I begin with the idea of “dancing at the edge of chaos” as a metaphor for adaptive living in a world characterized by constant change and uncertainty.

Your chances for successful living are optimal when opposing forces—tradition versus innovation, stability versus growth—are balanced through adaptability and compromise, rather than through rigid resistance to adaptive change.

Future posts will draw upon systems thinking as we create models for navigating the tension between stability and change as related to self-identity, social relations, cultural norms, and political polarities.

And yes, stability through change is a koan.

Life’s Path on a Fitness Landscape

Picture your life as an uphill journey on a mountain trail. Sometimes the slope is gentle, revealing calm meadows nearby. At other times, the hill becomes steep and treacherous. Adding to the challenge, your path often makes sharp turns, preventing you from seeing what’s ahead. Depending on your taste for risk, you are excited by the blind turns and charge ahead, or you step cautiously around the turn and into the unknown.

When thinking about traveling on an unfamiliar mountain path, you might envision plodding along, one step at a time, with heavy gear to aid your survival in challenging terrain with unpredictable weather. Not so on life’s path. There, it’s better to dance than to plod. Every person has a unique rhythm for their life. For some, it’s fast, and you relish the fast pace. For others, it’s as slow as paint drying on a wall - and that’s the way they like it.

No matter your life’s rhythm, whether fast or slow, dancing along your path means staying light on your feet—remaining flexible and adaptable. Many people prefer to push forward with heavy burdens rather than learn to dance in harmony with their unique rhythms. I encourage you to dance rather than plod.

Dancing at the Edge of Chaos

In a series of posts that will make up my book project, I will introduce you to the advantages of adaptive living on the edge of chaos.

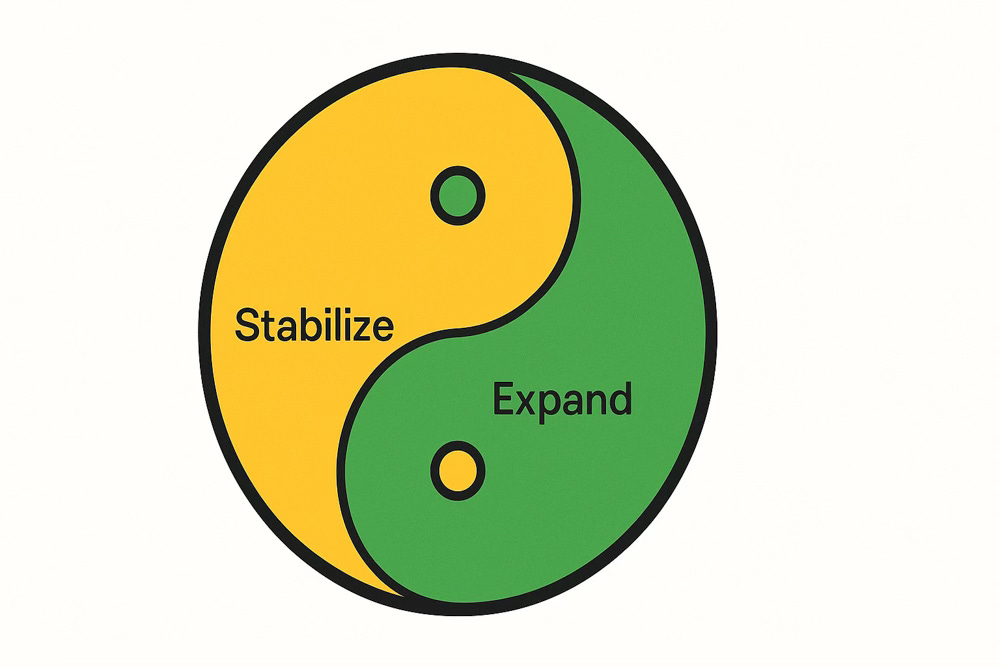

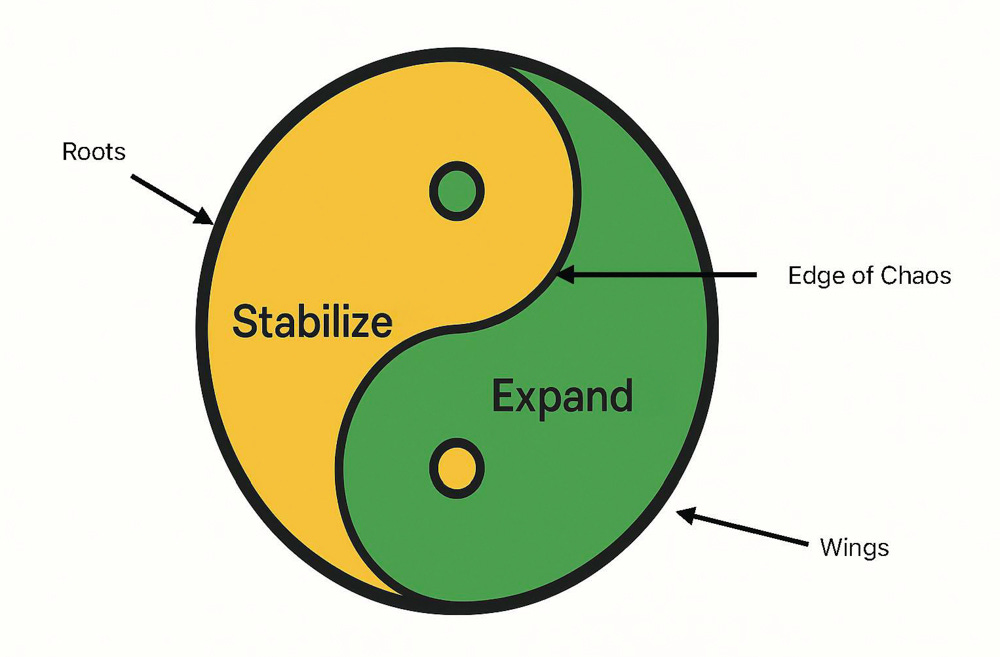

I’ll explain the stabilize/change logo,

Chaos refers to coping with life’s uncertainties. In the chaos of everything familiar being tossed into a jumbled heap, there are no rules. We need to either reestablish the old rules or create new ones.

The edge of chaos is the mental space that balances living in the past versus exploring the new. The tug between old and new can occur inside our minds, between people, or between social institutions (such as political parties).

Dancing is the art of reconciling the friction between parties that want to preserve some tradition versus finding new ways to solve problems. Opposing parties generate optimal outcomes when both sides stay light on their feetby being flexible, adaptable, and willing to compromise.

Even Starlings Dance at the Edge of Chaos

The dynamics of living at the edge of chaos can be found everywhere in nature, not just in humans. We can think of all forms of organic life as complex natural systems. In the struggle for existence, all living systems must learn how to cope with the stability that is challenged by the harsh conditions of nature. Living systems that learn to adapt to their new conditions have the best chance of survival.

This systems thinking perspective allows us to identify the simple rules of adaptation that underlie complex survival behaviors. Take, for example, a vast swarm of starling birds that can darken a bright sky by flying together, shape-shifting clouds that appear to be high on methamphetamines. A swarm of starlings is an example of complexity - but in complexity, we find simplicity.

Known as murmations, hundreds of thousands of starlings can fly together as one body because each starling follows a simple set of three rules.

Separation: maintain a minimal distance from immediate neighbors to avoid collisions,

Cohesion: move toward distant flockmates to preserve group unity, and

Alignment: match the speed and direction of the adjacent bird.

That’s it. Three simple rules that every bird follows. From these three simple rules, complex group behavior emerges—without a leader. When grouped on a trajectory of stable flight, a few starlings notice the threat of a falcon, which is communicated to the others. Each starling responds by following the rules and changing direction near-instantaneously.

Within the flock, there is no friction in the decision to change the direction of their flight. If they disagreed with one another, the flock would become a fragmented chaos and the falcon could easily pick off the birds who got separated from the flock.

Stability Through Change: The Key to Healthy Living for You, Social Relations, and Societies

One of the central principles of successful living—however you define it—is maintaining a dynamic balance between stability and change, and finding ways to resolve conflicts between the two with the least amount of stress. This challenge to achieve stability through change has been debated since the time of the ancient Greeks.

Around 500 BCE, the philosopher Heraclitus wrote about a world in a state of constant flux. He is often quoted as saying:

You can never step into the same river twice, because the river is never the same—and you are never the same.

Heraclitus lectured on the unity of opposites and the ongoing tension that arises from this interplay—day becomes night, peace gives way to war, and life gives way to death. As life’s circumstances change, we must adapt to the flux of each recurring phase of life.

Centuries later, in the late 1700s, German writer Johann Wolfgang von Goethe offered this well-known reflection:

“There are only two lasting gifts we can hope to give our children. One is roots, the other, wings.”

Goethe’s poetic hope was to offer children both the grounding of roots and the freedom of wings. However, as beautiful as it sounds, Goethe’s wish is a paradox. How can a child have roots and wings at the same time? Can you imagine a carrot soaring through the sky while still anchored in the ground?

We cannot possess roots and wings at the same moment in time. However, we can alternate between them. The wisdom of life lies in learning when to stand firm and when to let go.

Friction at the Flux of Stability and Change

The concept of dancing at the edge of chaos can be illustrated as a unity of opposites, where, like night giving way to day, stability gives rise to expansion, and expansion ultimately returns to stability.

If you recognize this image as a knockoff of the yin-yang mandala, you are right! The ancient Chinese concept of yin-yang parallels Heraclitus’ idea of the unity of opposites, as well as Goethe’s gift of roots and wings. In the yin-yang paradigm, Chinese philosophers envisioned opposing cosmic forces that continuously interact, connect, and sustain each other. In our example, these opposites represent two states of mind - our need for stability in life (yin) and our need to grow (yang).

We find that the edge of chaos is the mental space where changing life’s circumstances require adaptive decision-making. The choices between the old and new can be fraught with risk, or they can create exciting opportunities. I recently met a man at a party who is an urban planner. His history includes working for several years with a city planning board, becoming restless, and seeking a new job in another city, where he starts all over again.

While my new friend loves the excitement of change, others get mired in the present and close their eyes to new but necessary options. My sister, who passed away at the age of 82, lived in the same house where she was married and raised her seven children. Disabled, she was hospitalized and needed to be moved to a nursing home. She died the next morning after I gave her the bad news that she could not return to her home of more than 60 years. A change that would sustain her life was not an option for her.

Exploring Examples of Friction at the Edge of Chaos

We have observed that the mental space at the edge of chaos between stability and change can be thought of as tectonic plates rubbing against each other. The friction causes tension that can be released by “little earthquakes” that often go unnoticed. However, when the two opposing plates refuse to yield, the friction increases and suddenly breaks, resulting in a catastrophic earthquake.

A few examples help illustrate friction at the edge of chaos in three scenarios: personal, social relations, and national politics.

Personal: Ida is a young woman deciding on her career options. Her parents are lawyers, and her family has a long history of members being lawyers or judges. Her strong-willed parents expect her to follow the family tradition in law. However, Ida has always been drawn to technology, is fascinated by the new frontiers in the AI industry, and aspires to pursue a career in electrical engineering. Her stable mindset advises her to obey her parents’ wishes, but her expansive mindset yearns for a different life. After much internal debate fueled by anxiety and guilt (personal friction), Ida decides to inform her parents of her decision not to become a lawyer. After much discussion, sometimes heated (due to relationship friction), they accept Ida’s decision and offer their support.

Relational: Here’s a true story example. My wife of 45 years and I share many interests, but we also have our differences. I am an early adopter of all things tech, while she is a late adopter. In the early days of the Apple ecosystem, I began switching all our home devices from PCs to Macs, including computers, watches, and iPhones. Although my wife loved her iPhone, she refused to give up her PC laptop because it was familiar to her (stability). It wasn’t until her ancient PC began breaking down (a life circumstance) that I was able to convince her to get a Mac laptop. She did, and now it’s part of her device ecosystem (friction resolved, expansion successful).

Another lesson is that the dynamics of stability and change are domain-specific. While my wife is a slow adopter of technology, she is a super-early adopter of cultural trends (innovation), whereas I am a cultural neanderthal (comfortable with my cultural fog). However, because I am willing to follow her lead in visiting museum exhibits, we have been able to minimize the friction between her early adoption of nouveau arts and my late adoption of strange-to-me art forms.

Political: In this final example, which takes place on the State of Washington’s Olympic Peninsula, we see the logging Murphy Company at loggerheads with environmental protesters. A year ago, Murphy Co. was awarded a public contract to harvest old forest and had already invested $1.3 million in preparation for the logging (creating a stabilizing investment). In a protest against the prospect of logging old forest, environmentalists erected a platform on a tree 80 feet above the ground. The protesters connected the suspended platform by wire to a barrier in the road, such that if the barrier were pushed away, the platform would fall, killing the occupying protesters. This was a novel solution to the traditional logging subterfuge of protests.

After 40 days of platform occupation, a violent confrontation ensued between unidentified loggers and protesters, an encounter involving gunshots and death threats (a tectonic plate earthquake between stability and change). Although no one was hurt, the environmentalists abandoned their platform because of safety concerns.

In subsequent legal action, the court ruled in favor of industrial stability by upholding the Murphy Co. contract and rejecting the protesters’ claims. The great friction in this dance at the edge of chaos ended with the logging company’s stability winning over the protesters’ demand for change.

From these examples, it is clear that the mental space at the nexus of stability and change can occur within a person’s mind, between parties in a social relationship, or between conflicting social organizations, such as a logging company and environmentalists.

These conflicts are best resolved when parties are willing to be flexible. Too often, instead of adapting easily, it only takes one side to dig in, and the conflict continues. Sadly, this deadlock defines the political interactions of many countries involved in ideological or hot wars.

Summing Up

In future posts, I will delve further into how the human mind, both individually and in social contexts, resolves conflicts between those who favor stability and those who advocate for change. These conflicts are as old as civilization, and we have more than our share of these conflicts in today’s world.

I will also introduce models of how the human mind operates to create and solve problems related to stability and change. With these mind models, you will gain a deeper understanding of how your own mind functions. You will also discover how millions of people can develop views of reality that are completely opposite to millions of others who share your worldview.

And speaking of reality, my next post will show that, in today’s world of political polarities, partisan newsfeeds, and conspiracy theories…

Reality ain’t what it used to be.

Follow this series of posts in this Edge of Chaos series that I publish on Medium, Substack, and my website, Upuzzling Life’s Complexities. On my website, you can subscribe to get each post delivered to your mailbox at no cost.